Percentage of North Carolina 16-24-year-olds neither in school or working (indicator shown as distance from 100%)

Last updated: 2023

= Top southern state :

only available for totals, not available for all indicators

What does Opportunity Youth mean?

Percentage of North Carolina 16-24-year-olds neither in school or working (full or part time). This figure includes incarcerated youth who are not enrolled in school.

What does this data show?

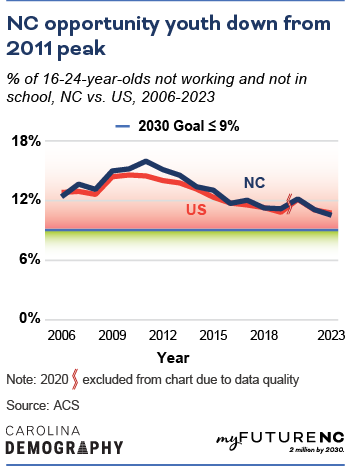

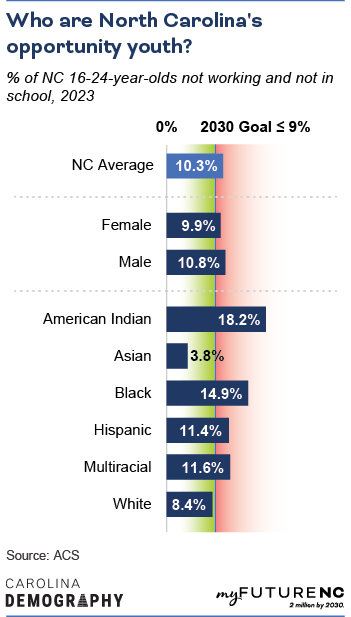

Just above one in every ten (10.3%) North Carolina 16-24-year-olds were not in school or working in 2023, placing our state 25th among all states for opportunity youth. In Virginia, the southern state with the lowest levels of opportunity youth, this rate was 8.9%. North Dakota had the lowest rate of opportunity youth of any state nationwide (4.8%).

By 2030, the goal is to have 9% or less of 16-24-year-olds neither working nor in school, meaning 91% or more will be working or in school.

Why does Opportunity Youth matter?

Ages 16-24 represent a critical period in the transition to adulthood—higher rates of opportunity youth suggest these young adults are cut off from critical social supports and experiences that can help them build a path to the future.

Opportunity youth may also be referred to as disconnected youth. Measure for America, a project from the Social Science Research Council, notes that disconnected youth are “cut off from the people, institutions, and experiences that would otherwise help them develop the knowledge, skills, maturity, and sense of purpose required to live rewarding lives as adults. And the negative effects of youth disconnection ricochet across the economy, the social sector, the criminal justice system, and the political landscape, affecting us all.”

An analysis of disconnected youth in the Research Triangle by MDC, Inc. found that disconnected youth may:

- struggle in school or perform below grade level

- be less prepared for the labor market

- live in high-poverty families, often headed by a single parent

- be in or exiting foster care

- be at-risk of sanction by the criminal justice system

Unemployment and a lack of educational attainment is also linked to depression, anxiety, and isolation. The limited education, lack of work experience, minimal professional networks, and social exclusion of opportunity youth have consequences into adulthood and may affect earnings and self-sufficiency, physical and mental health, and relationship quality and family formation.

How is North Carolina performing?

Meeting the 2030 Goal

North Carolina needs 17,468 more 16-24-year-olds working or in school to meet the statewide goal.

North Carolina’s rates of opportunity youth were similar to the national average— 10.3% of people aged 16-24 were not working or employed in 2023 in North Carolina, close to the national rates (10.6%). Statewide opportunity youth rates were above the national average in every year between 2006 and 2015 but have drawn closer to the national average in recent years. Statewide, the share of opportunity youth follows national patterns: peaking after the Great Recession (2010 nationally and 2011 in NC) and trending downward until 2019. In both North Carolina and nationally, the share of opportunity youth fell from 2022 to 2023 (by 0.6 percentage points in NC and 0.3 percentage points nationally).

By sex

North Carolina women ages 16-24 had slightly lower shares of opportunity youth compared to men ages 16-24 (9.9% vs. 10.8%).

By race/ethnicity

American Indian youth ages 16-24 had the highest shares of opportunity youth—18.2%—meaning they were least likely to be in school or working. Black (14.9%), Multiracial (11.6%), and Hispanic (11.4%) youth both had disconnection rates above the state average. White (8.4%) and Asian (3.8%) youth age 16-24 were the only groups to meet the state goal of 9.0% or below.

Methodology

Where does the data for opportunity youth come from?

The U.S. Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey (ACS). This annual survey of demographic, economic, and social characteristics has been collected for all households and group quarters populations since 2006. The Public Use Microdata Series (PUMS) contains anonymized person-level observations that enable custom tabulations of the data for the state and some counties.

How was the data calculated?

Carolina Demography calculated the opportunity youth rate using ACS 2023 1-year PUMS data retrieved from the U.S. Census Bureau. Individuals were identified as being opportunity youth if they were not enrolled in school and were either unemployed or not in the labor force. The opportunity youth rate was calculated by dividing the estimated number of opportunity youth ages 16-24 by the total number of youth ages 16-24.

Who is included?

All residents of North Carolina ages 16-24.

Who isn’t included?

Certain types of group quarters facilities are not sampled due to difficulties associated with data collection, such as domestic violence shelters, soup kitchens, and living quarters for victims of natural disasters. Full details on the ACS sample and methodology are available here.

The data used in the development of this indicator is derived from a survey and is subject to sampling and non-sampling error.

Learn more

Who is working on this in NC?

Help improve this section

If you know of an organization that is working on this topic in NC, please let us know on the feedback form.

NC-focused, state-level dashboards

Name: NC Workforce Development Board Dashboard

Website: https://bi.nc.gov/t/COM-LEAD/views/NorthCarolinaWDBDashboard/ImpactsSummary

About: This tool displays information on the services rendered, participants served, and outcomes achieved through the state’s Workforce Development Boards.

Name: NC Labor Supply/Demand Analyzer

Website: https://nccareers.org/s-d/

About: Developed by the NC Department of Commerce, this tool tracks the tightness of the state’s labor market and view estimates of the number of jobseekers and job openings.

Name: NC Works Labor Market Indicator Dashboard

About: Find Labor Market Information Data such as occupation information, wage information, unemployment rates, advertised job posting statistics, demographic information, and more.

Further research and literature

AIR. (2024). An Opportunity to Do Better: Youth Pathways to Thriving. Arlington, VA. AIR.

CLASP. (2012). Out-of-School Males of Color: Summary of Roundtable Discussion. Washington, DC: CLASP.

Lewis, Kirsten, & Gluskin, R. (2018). To Futures: The Economic Case for Keeping Youth on Track. New York: Measure of America, Social Science Research Council.

Lewis, Kristen, & Burd-Sharps, S. (2015). Zeroing In on Place and Race: Youth Disconnection in America’s Cities. New York: Measure of America, Social Science Research Council.

Martha Ross and Nicole Prchal Svajlenka. (2016). Employment and disconnection among teens and young adults: The role of place, race, and education. Washington, DC: Brookings.

Mason, D. (2019, March 14). Engaging “Disconnected” Youths to Prevent Lives of Isolation, Poverty, and Ill Health. news@JAMA. Retrieved December 12, 2019, from https://newsatjama.jama.com/2019/03/14/jama-forum-engaging-disconnected-youths-to-prevent-lives-of-isolation-poverty-and-ill-health/

MDC, Inc. (2018, August). Disconnected Youth in the Research Triangle Region: An Ominous Problem Hidden in Plain Sight. Retrieved December 18, 2019, from https://www.mdcinc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/disconnected-youth.pdf

MDRC. (2013). Building Better Programs for Disconnected Youth. New York: MDRC.

U.S. Department of Education. (2017). Supporting the Educational and Career Success of Out-of-School Youth under WIOA. Washington, DC: Office of Career, Technical, and adult Education, U.S. Department of Education.

FAQ

Are individuals who are incarcerated classified as opportunity youth?

Individuals who are incarcerated and are not reported as being enrolled in school or working will be identified as opportunity youth.